Part 1: Père Lachaise

Paris’ largest (43 hectares/106 acres) and most famous cemetery merits a separate outing as there’s just so much to see. I used to live nearby (quietest neighbours, EVER), and it was my local park: I used to come here all the time for a stroll, or just to sit and read.

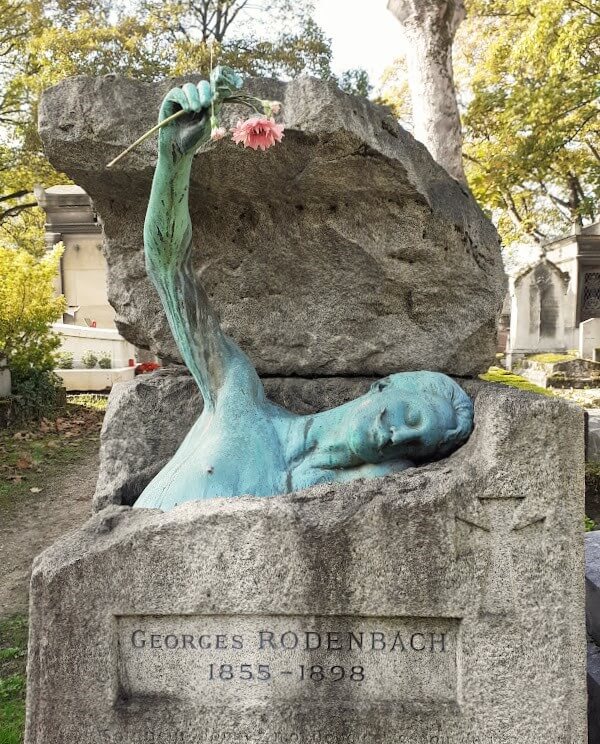

Most visitors tend to make a beeline for the tombs of Jim Morrison and Oscar Wilde. But there are scores of treasures here, from the mausoleum of star-crossed medieval lovers Héloïse and Abélard to Georges Rodenbach’s fascinatingly creepy grave.

It’s a classic love story: Boy meets girl. Girls gets pregnant and gives birth. Boy and Girl marry in secret to avoid damaging Boy’s career in the church. Girl’s evil uncle finds out and has Boy castrated. Boy and Girl retire to a convent/monastery for the rest of their lives.

The 12th-century blue stocking and nun Héloïse and her tutor-turned-lover-turned-husband, Pierre Abelard, a renowned and respected mathematician and theologian, were originally buried elsewhere but their remains were moved to Père Lachaise in 1817.

Indeed, Père Lachaise is steeped in romantic – and Romantic – folklore: it’s a key stage on my Romantic pilgrimage to Paris. For in addition to the many writers, musicians and artists of the Romantic movement – Chopin, Alfred de Musset, Gérard de Nerval, Eugène Delacroix, Théodore Géricault (below), Bizet – you can also find the graves of people who lived – and died – in accordance with Romantic tenets, such as Victor Noir (left), an anti-imperialist journalist who was killed in a duel at the age of twenty-one by a cousin of Napoleon Bonaparte. His tomb has since attracted hordes of rather bizarre groupies: I’ll let you draw your own conclusions when you see which parts of his anatomy have been worn away and polished in the photo...

The cemetery is also the final resting place of many notable musicians including Rossini, Bellini (although strictly speaking, only their tombs are here: their remains were eventually transferred back to their native Italy) and Edith Piaf, who was born and spent the first few years of her life less than a kilometre away, as well as literary giants such as Molière, Balzac, Colette (right), Proust, Jean de la Fontaine – and of course, Oscar Wilde.

Wilde’s dramatic descent from successful man of letters, leading figure of the Aesthetic movement and darling of fashionable London society into scandal, social ostracization, imprisonment, exile and poverty has been extensively documented. After serving two years’ hard labour (the punishment for homosexuality at the time), with his marriage, finances and reputation in tatters and his health irretrievably diminished, Wilde fled to France where he spent his wretched final years. He died there in 1900, but continued to be the subject of scandal and controversy for years after his demise. Originally buried at Bagneux cemetery, his remains were later moved to Père Lachaise. Then in 1908, a wealthy benefactress sent Robert Ross, Oscar Wilde’s former friend, one-time lover and now the executor of his estate, £2,000 to erect a monument for Wilde at Père Lachaise – on the condition that the sculpture be carried out by the Anglo-American sculptor and painter Jacob Epstein (1888-1959). For the young Epstein, this prestigious project was one of his first major commissions. The sculpture, a naked, winged Sphinx-like creature, probably inspired by Wilde’s poem “The Sphinx”, was completed in London in 1912 – some twelve years after the writer’s death.

“Come forth my lovely seneschal!

So somnolent, so statuesque!

Come forth you exquisite grotesque!

Half woman and half animal!Come forth my lovely languorous Sphinx!

And put your head upon my knee!

And let me stroke your throat and see

Your body spotted like the Lynx!”Oscar Wilde, “The Sphinx”

Unfortunately, and to Epstein’s dismay, the sculpture was caught up in a maelstrom of red tape, controversy and censorship the minute it crossed the English Channel. In short, the French hated it. They were offended by the exposed genitalia and banned it: it was subsequently covered with a tarpaulin and guarded by a gendarme. A lengthy battle between Epstein and the French authorities ensued, with countless petitions, protests and newspaper articles. As a gesture of appeasement, Ross had the offending genitalia covered (to Epstein’s outrage) by a brass butterfly, which was later removed by one of the artist’s allies. The testicles themselves were eventually chipped away and sadly, the tomb was continually defaced by graffiti and lipstick marks for decades, until 2011 when it was restored, courtesy of the Irish government and the Ireland Fund of France. It is now an historic monument and protected by a glass screen.

In addition to boasting the tombs of countless artists and writers, Père Lachaise is of considerable historical and political significance, with commemorations of some of the bleakest periods in history. The Communards’ Wall (Mur des Fédérés) honours the memory of the 147 soldiers of the Commune, the revolutionary government that seized power in Paris from 18 March to 28 May 1871 (and, in Karl Marx’ opinion, the only example in the history of France of a dictatorship of the proletariat), which ended on May 28, 1871, during the aptly named Semaine Sanglante (“Bloody Week”). The soldiers, known as fédérés, were executed against a wall of the cemetery by the Versailles troops and buried in a mass grave at the foot of the wall.

There are also a number of harrowing memorials erected for the victims of the Bergen-Belsen, Dachau, Auschwitz and Sachsenhausen-Oranienburg Nazi concentration camps.

Aside from its countless famous (what do we call them: residents? Denizens? Tenants?), the cemetery features a number of curiosities in the form of some elaborate, eccentric, and, in some cases, downright macabre tombs and mausolea. The grave of Georges Rodenbach, (right), a Belgian Symbolist poet and novelist, for example, shows him emerging, Night of the Living Dead-like from his tomb, clutching a rose in his hand.

/

Weird random anecdote. Years ago, during one of my frequent walks around Père Lachaise, I came across an English tourist who appeared to be talking to someone (or something!) inside one of the mausolea. As I approached, I saw that she was indeed talking to her mother who had, somewhat ill-advisedly, gone into the tomb to explore when the floor had collapsed beneath her feet. She had fallen several feet down and now just her head was poking out of a hole in the ground. She had hurt her ankle and was visibly (and understandably!) shaken and as neither she nor her daughter spoke French, I called one of the cemetery guards who subsequently called the fire brigade. I stayed to interpret and try and reassure them until the firemen came and rescued the unfortunate lady.

Moral of the story: er, don’t go wandering into people’s tombs.

Oh, and one last thing. My grandparents were buried here. But that’s of limited interest to anyone but me.

Part 2: Montmartre, Montparnasse and Charonne

One thought on “Paris’s Most Illustrious Dead: Luc’s Cemetery Tour”